Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic Cancer: Causes, Risk Factors, Prevention, Genetics, Family History, Stages, and Treatment

Dhairya Patel, Rayyan Syed (CO-Authors),

and Dr. Lopamudra Das Roy

Published 2022

@BreastCancerHub, All Rights Reserved

Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is among the most lethal of all cancers. Due to its silent spread, the cancer often goes through the first stages without it being detected. Early diagnosis is often very difficult to obtain and the cancer often gets detected only after it has spread to other body regions such as the organs in the abdomen like the liver, gallbladder, etc. This research paper will analyze and educate different aspects of this cancer. The paper will explain thoroughly the stages, cause, risk factors, treatment options, and genetic/familial components. It will also educate and identify any trends between socioeconomic and global statistics with the rate and treatment of pancreatic cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Additionally, it incorporates the connection between socioeconomic conditions and effect of diagnosis as well as lifespan longevity. In conclusion, the paper will deeply analyze the components of pancreatic cancer and explain certain trends associated with lifestyle and socioeconomic situations.

Causes

Pancreatic cancer is classified by medical providers as an idiopathic illness, this means that the cancer does not have a definite cause but can include certain risk factors and/or probable causes [1,2,3]. Currently registered with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there are several phase III trials currently aimed at finding the biomarkers associated with the cancer. Though the current medical community cannot give a specific cause they do however, know that it is caused by a gene mutation that can be acquired genetically or environmentally. It should be noted that there is still no complete determination of the oncogenes trigger in the first place [2].

Risk Factors/Prevention

As of 2022 there are close to 40 phase III FDA trials concerning pancreatic cancer. All of which aim to find or recycle a past medication to manage and cure the cancer [4]. Because of these trials, researchers have discovered certain risk factors concerning this cancer. From lifestyle or genetics, the risk of an individual getting pancreatic cancer is rare affecting 13 out of 100,000 people [4].

Lifestyle risk factors include those which are concerning diet, health, environment and habits. These include: diabetes, smoking, race (ethnicity), obesity, pancreatitis including chronic and hereditary, old age, diet and food choice, chemical and heavy metal exposure (environment) and gum disease [4,5]. Research has shown that individuals who have had diabetes for more than 5 years or are older than 50 years and have had a sudden onset of type 2 diabetes with low body max index may be at risk for pancreatic cancer [5]. Since the pancreas is what controls our insulin output, diabetes can damage the pancreas to the point where cancer cells may start growing. Another risk factor is smoking, it can cause significant exocrine damage including pancreatic cancer and it is proven that individuals who smoke cigarettes are two times more likely to develop this cancer [4,5,6]. Pancreatitis can also pose a risk factor as a prolonged inflamed pancreas can lead to more damage and eventually into cancer. This is most commonly seen in hereditary pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis that is developed from alcohol abuse [5]. Finally, a diet that is high in red and processed meats can also lead to pancreatic cancer as those foods not only cause diabetes and obesity but can also damage the pancreas. Other risk factors include the environment if there is heavy chemical and metal exposure to:

Beta-naphthylamine

Benzidine

Pesticides

Asbestos

Benzene

Chlorinated hydrocarbons

These chemicals are common in damaging the pancreas and can also cause genetic changes leading to pancreatic cancer [4,5]. Lastly, gum disease is the final lifestyle risk factor. Periodontal disease and tooth loss are marked as a risk factor for unknown causes even when other factors are not present [4,5].

Ethnicity

In terms of demographics, ethnicity and race are major risk factors for pancreatic cancer. For example, studies show that patients of African ancestry are 20% more likely to develop pancreatic cancer than other races such as whites, Asians, or Hispanics [7,8,9,10]. And individuals of Jewish ancestry tend to be more likely to possess a mutation in the BRCA2 gene, which, as mentioned in the “Genetics'' section of this paper, is a leading cause of pancreatic cancer [11]. The incidence rates of these two ethnic backgrounds are substantially higher than those of other races, which means early screening and awareness of pancreatic cancer in Jewish and African populations is crucial to prevent the escalation of pancreatic cancer in Jewish and African individuals and to ensure their proper health and wellbeing.

Socioeconomic Factors

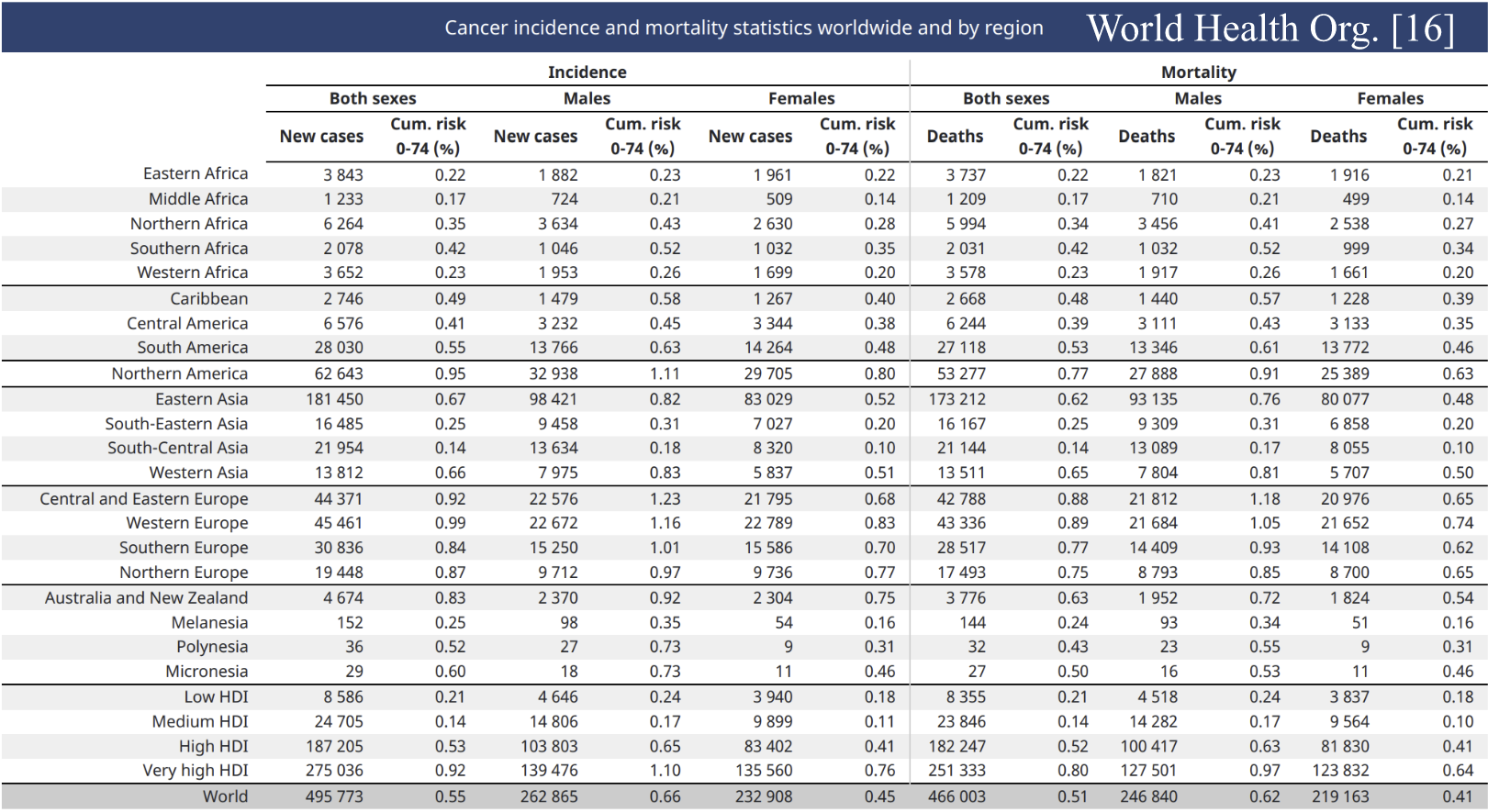

Pancreatic cancer has not been researched enough to come to a definite conclusion of whether it is affected by socioeconomic (SES) reasons. However, there is credible information suggesting that lower SES areas see more deaths in this type of cancer because of a variety of items. Such as lower SES areas not having enough medical coverage or even insurance for inpatient/outpatient wellness visits and procedures [4]. Many also are limited to seek medical care till the problem persists for a long time because of their monetary restrictions. In fact, a low SES area has been shown as an independent risk factor in many cases and studies. [3] The chart shows how the highest cases tend to be in the more lesser developed countries such as Eastern Africa, South America, South-Eastern Asia, and Central and Eastern Europe [10]. In accordance, those areas also have the most mortality rates as well. Thus it can be inferred that lower SES areas due to their lower wages, less insurance, and tight monetary restrictions can lead to a lesser life expectancy with pancreatic cancer and a delayed diagnosis of it [10]. In conclusion, lower SES areas tend to have higher cases of pancreatic cancer and within this they also may have lower life expectancy then when compared to high SES areas.

Lifestyle/Environmental Factors

A patient’s lifestyle can have a large impact on whether they develop pancreatic cancer. Although a majority of pancreatic cancers are caused by factors which are out of a patient’s control, such as DNA copying errors and family histories of pancreatic cancer, a significant 20% of pancreatic cancers are caused by a patient’s poor lifestyle choices and harmful living/working environment [11].

One major lifestyle-based risk factor of pancreatic cancer is tobacco use [7,9]. Regular smokers who use cigars, pipes, and/or smokeless tobacco products are twice as likely to develop pancreatic cancer than people who do not smoke [7,9]. In fact, 25% of pancreatic cancers are believed to be caused by smoking [7]. Smoking, and especially heavy alcohol use, can often lead to a condition known as chronic pancreatitis, a long-term inflammation of the pancreas [7]. Chronic pancreatitis can actually lead to, and makes individuals more vulnerable to, pancreatic cancer [7]. Luckily, the risk for pancreatic cancer decreases when a person stops using tobacco products [7].

Another lifestyle-based risk factor is being overweight [7]. Obese people and individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more are 20% more likely to develop pancreatic cancer [7]. Even if an individual is not considered “obese” according to their BMI, any adult with extra weight around the waistline is also more likely to develop pancreatic cancer than an individual with a regular, controlled weight [7]. Obesity is often linked to pancreatic cancer as excess fat tissues in overweight people produce more hormones, such as insulin [5]. These hormones, which are made in the pancreas, increase the risk of cancer development through inflammation, insulin resistance, and altered intestinal microbiota [5,10]. This further creates a link between patients with diabetes and the chance of developing pancreatic cancer [10].

A common environmental risk factor of pancreatic cancer that many don’t realize can be a risk factor is the workplace of an individual [7,9]. People who work in dry cleaning or metalworking industries may have excess exposure to harmful chemicals. Studies show that people who have been exposed to these harmful industrial chemicals actually have an increased risk of pancreatic cancer [7,9].

Genetics/Family History

Family history and genetics are known to be a risk factor for pancreatic cancer and help in determining whether an individual is susceptible to developing pancreatic cancer later in life. Pancreatic cancer tends to run in the genetics of some families, and this increased risk is caused by inherited syndromes and gene mutations [7]. Roughly 5% to 7% of pancreatic cancer patients possess a gene mutation in the BRCA1, BRCA2, p16, PALB2, PRSS1, MLH1, MLH2, STK11, ATM, and CDKN2A genes, and a mutation in these genes is typically an indicator of a potential pancreatic cancer [4,7,12]. Another gene in familial cases, resulting in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, is the oncogene KRAS. This gene stays active while simultaneously the tumor-suppressor genes CDKN2A and SMADA were inactivated. This results in the growth of cancer cells at the same time genes dealing with tumor suppression are inactive. Therefore, in commonality, the biggest risk factor and potential biomarker of pancreatic cancer would be the activation of the KRAS oncogene. In addition, a family history of Lynch syndrome, chronic pancreatitis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, or familial atypical mole-malignant melanoma (FAMMM) can also increase the risk for pancreatic cancer [7,13]. However, even if someone has a family history of the above genetic syndromes or a mutated pancreatic cancer gene, the chances of pancreatic cancer actually developing is a mere 10% to 25%, which explains why pancreatic cancer is a rare cancer to encounter [11]. Nonetheless, pancreatic cancer screening is crucial if an individual is found to possess any of these genes or syndromes [11].

Stages

Staging of pancreatic cancer is most commonly classified using the AJCC’s (American Joint Committee on Cancer) TNM system [12]. The TNM system can be broken down into three parts: tumor (T), nodes (N), and metastasis (M) [12]. The T in the TNM system represents the extent to which the pancreatic tumor has grown in the pancreas, as well as in surrounding areas and blood vessels [12]. The N stands for the spread of the cancer to nearby lymph nodes and how many lymph nodes have the cancer [12]. And the M represents the spread of the cancer to distant lymph nodes and organs, also known as metastasis [12]. These three factors are ranked using numbers to determine the severity of each factor. As seen in the image “Clinical staging,” the stage of each TNM factor combines to create an overall AJCC stage [12]. These AJCC stages range from stages I (1) through IV (4), and the lower the stage number, the less the cancer has spread in the patient [12].

It is important to note that the AJCC stages in the table above are part of the greater pathologic stage, also known as the surgical stage [12]. If the pancreatic cancer tissue is small enough to be surgically removed during an operation, then the cancer is considered to be in the pathologic stage [12]. However, if the cancer has already spread to nearby organs or found to be too large to be surgically removed, then the cancer is said to be in the clinical stage [12]. But how do oncologists know how advanced the pancreatic cancer is?

While there are several ways to assess the spread of pancreatic cancer, most commonly, oncologists conduct staging laparoscopy procedures [14]. This procedure involves a surgeon making small incisions in the abdomen to insert a thin, tube-like instrument which has a camera on the end. This camera-equipped tube will allow the surgeon to see the pancreas, observe how much the cancer has spread, and determine the cancer’s stage [14].

Although the TNM and AJCC systems are most often used by oncologists to assess a patient’s cancer stage, there are other factors that are also crucial in determining the severity of the patient’s pancreatic cancer: one factor being tumor grade [11,12]. This grade describes what the cancer looks like under a microscope [12]. On one end of the grading spectrum, Grade 1 (G1) implies that the cancer tissue is visible, but most importantly, has not spread to nearby areas [11,12]. On the other end, Grade 3 (G3) means the pancreatic cancer looks abnormal and that a cancer-esque growth is evidently visible and has spread to distant areas as well [11,12]. Any pancreatic cancer which visually falls in between these two categories is considered to be Grade 2 (G2) [12].

Those patients who have had surgery to remove the pancreatic cancer must be aware of another factor which affects the stage of the tumor: extent of resection [12]. The extent of resection refers to the degree/extent to which the cancerous tumor has been removed from the patient [12]. There are three stages regarding the extent of resection. Stage R0 implies that all of the pancreatic cancer has been completely removed and that there are no visible or microscopic signs indicating the existence of cancer [12]. Stage R1 means that although all the visible cancer was removed, lab tests show microscopic remnants of the cancer were left behind [12]. And finally, Stage R2 implies that visible and microscopic remnants of cancer were left behind and could not be removed. [12].

All this considered, new research has shown that, contrary to past beliefs, pancreatic cancer actually develops and spreads slowly [14]. After the first cancer cell appears, it takes approximately seven years for that cancer cell to multiply into a tumor the size of a plum [14]. After the full development of the tumor and its spread to other organs, patients die from the metastasis of their pancreatic cancer after an additional 2.5 years [14]. Due to pancreatic cancer’s relatively late metastasis, in total, it takes pancreatic cancer an average of 9-10 years to kill a patient from the birth of the cancerous cell to the patient’s death [14]. However, while this may sound like a long time, the reason pancreatic cancer can be so deadly is due to its late detection [13]. The truth is imaging can often miss the tumor and offering imaging to someone who does not experience symptoms in the first place can be difficult and expensive [13]. New technology, such as blood biopsies, are still under development, and it is safe to say the future of the early detection of pancreatic cancer lies in the hands of new screening technologies when they eventually arise [13].

Treatment

Once one is diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, it is important to look to the future and treat the individual's cancer using several treatment methods. Firstly, it’s crucial to make an attempt to surgically remove the cancer from the patient. There are two types of surgery which can be used for pancreatic cancer: potentially curative surgery and palliative surgery [14].

Potentially curative surgery is done when exam and screening results show that it is possible to remove all the cancer from the pancreas [14]. This surgery is very complex and might take weeks or months to fully recover from it [14]. Removing only a part of the tumor does not extend a patient’s life, so this surgery should only be performed after the patient’s surgeon is confident that all the cancer can or cannot be removed and that the patient is fully aware of the long recovery, risk, and potential side effects [14]. Note that this surgery is rare as only 1 in 5 pancreatic cancers are confined to the pancreas/easy to remove [14]. Even during this surgery, if the surgeon realizes that it is not possible to completely remove the tumor, they will continue the operation as a smaller, palliative surgery, which has its own side effects [14].

There are several procedures which surgeons can conduct as part of potentially curative surgery: Whipple procedure (pancreas head removal), distal pancreatectomy (pancreas tail removal), and total pancreatectomy (entire pancreas removal) [14]. During a Whipple procedure, also referred to as a pancreaticoduodenectomy, the surgeon makes a large incision down the abdomen completely removing the cancerous head of the pancreas, as well as parts of the small intestine, bile duct, gallbladder, and nearby lymph nodes [14]. Any parts of the remaining bile duct and pancreas are attached to the small intestine so that any bile is still able to proceed to the small intestine to help digest food [14]. It is important to note that there is a high risk of complications after this procedure which can be fatal [14]. Some complications include leaking between organs, infections, trouble digesting food, bleeding, and diabetes [14].

In contrast, a distal pancreatectomy is where the cancerous tail of the pancreas is removed, as well as the spleen [14]. The spleen helps the body fight infections, so its removal can increase susceptibility to certain bacteria after the procedure [14].

Finally, if the entire pancreas is cancerous (and not just the head or tail), surgeons may conduct a total pancreatectomy as part of the potentially curative surgery. As the name suggests, this operation removes the entire pancreas, as well as the entire gallbladder and parts of the small intestine and spleen [14]. However, this procedure is uncommon as, even though humans can live without a pancreas, the operation does not have major advantages, and in fact, has serious side effects and implications, such as taking pills to replace the role the pancreas played in digesting certain foods [14].

For those whose pancreatic cancer has already spread too far to be removed completely, then oncologists opt for palliative surgery. The intended purpose of palliative surgery is never to cure the cancer. Rather, it is done to relieve the patient of any pain or discomfort the tumor is causing [14]. There are two procedures that can be done as part of pancreatic cancer palliative surgery: stent placement and bypass surgery [14].

When pancreatic cancer spreads to the bile duct, the tumor blocks the bile duct, which hampers digestion and could lead to pain in the GI tract [14]. Thus, a stent placement is conducted to keep the bile duct open to allow digestion to continue almost normally and prevent jaundice [14]. This procedure is done using an endoscope [14]. The other procedure which can be done as part of palliative surgery is bypass surgery. Done on people who are healthy enough to withstand it, the operation doesn’t clear the blocked bile duct, but rather reroutes the flow of bile directly into the small intestine, “bypassing” the bile duct [14]. There are a few benefits of conducting bypass surgery compared to a stent placement. For one, bypass surgery can result in longer-lasting relief than a stent [14]. And during surgery, the surgeon might be able to cut some nerves around the pancreas and inject them with alcohol, numbing any pain caused by the pancreatic tumor [14].

In addition to the current surgical and chemotherapy drug treatments for Pancreatic Cancer, the FDA has many phase III trials in which newer medication combinations and surgical techniques are being tested. For example, in the last 2 decades ultrasonic tattooing has been growing as a pancreatic cancer treatment [3,6]. In this procedure they can localize small lesions before laparoscopic resection, this means that the procedure can give them a map of the cancer in the body before the resection surgery aimed to remove the tumor bed [3].

Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy options have also grown. Though the concept of adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy has been known for a long time, researchers are starting to find newer and better combinations of drugs, radiation, and surgical options to better handle pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant therapy is the therapy that is proposed as the main, and curative option whereas neoadjuvant therapy is a secondary therapeutic option usually given in preparation to the main adjuvant therapy. In most cases a neoadjuvant therapeutic option might be given before a curative resection surgery for an increased R0 rate [3,6]. Though the optimum neoadjuvant treatment plan has not yet been created, medical professionals usually prescribe chemotherapy combination schedules. This can include radiation and medication as well as multiple surgeries combined with medication.

References

[1] National Institute of Health: National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. (n.d.). Pancreas recent trends in SEER age-adjusted incidence rates, 2000-2019 [Fact sheet]. NIH. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html?site=40&data_type=1&graph_type=2&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&rate_type=2&race=1&age_range=1&stage=101&advopt_precision=1&advopt_show_ci=on&hdn_view=1&advopt_display=2#tableWrap

[2] Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. (n.d.). Pancreatic cancer risk factors. Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://pancan.org/facing-pancreatic-cancer/about-pancreatic-cancer/risk-factors/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw94WZBhDtARIsAKxWG-8r3gP8-eLKB26BFOCtaZ-NNPzwdLqXIhRJLoHM65suLUVlIPm4fJYaAvscEALw_wcB

[3] Park, W., Chawla, A., & O'Reilly, E. M. (2021). Pancreatic Cancer: A Review. JAMA, 326(9), 851?862. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.13027

[4] Rawla. (2019, February 26). Estimated age-standardized incidence and mortality rates (World) in 2018, pancreas, both sexes, all ages [Image]. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

[5] Ali. (2016, January 7). Obesity increases pancreatic cancer risk. In Pancreatic Cancer Action (Author), Pancreatic Cancer Action. Pancreatic Cancer Action. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://pancreaticcanceraction.org/news/obesity-and-pancreatic-cancer-risk/#:~:text=The%20fat%20tissues%20in%20overweight,certain%20cancers%20including%20pancreatic%20cancer

[6] Park W, Chawla A, O'Reilly EM. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021;326(9):851?862. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.13027

[7] The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. (n.d.). Pancreatic cancer risk factors. In American Cancer Society (Author), American Cancer Society. Retrieved August 27, 2022, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html#written_by

[8] Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Pancreatic cancer family history research. In Johns Hopkins Medicine (Author), The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center: Skip Viragh Center for Pancreatic Cancer. Retrieved August 27, 2022, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/cancers_we_treat/pancreatic_cancer/research/family_history_research.html

[9] Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Pancreatic cancer risk factors. In Johns Hopkins Medicine (Author), Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved August 28, 2022, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/pancreatic-cancer/pancreatic-cancer-risk-factors

[10] Xu, M., Jung, X., Hines, O. J., Eibl, G., & Chen, Y. (2018). Obesity and pancreatic cancer: Overview of epidemiology and potential prevention by weight loss. In National Center of Biotechnology Information (Author), National Center of Biotechnology Information (pp. 158-162).

[11] Cancer.Net Editorial Board. (2021, September). Pancreatic cancer: Stages. In American Society of Clinical Oncology (Author), Cancer.Net. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/pancreatic-cancer/stages

[12] The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. (n.d.). Pancreatic cancer stages. In American Cancer Society (Author), American Cancer Society. Retrieved August 27, 2022, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging.html

[13] Bender, E. (2020). Will a test to detect early pancreatic cancer ever be possible? Nature, 579, S12-S13. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00846-3

[14] The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. (n.d.). Surgery for pancreatic cancer. In American Cancer Society (Author), American Cancer Society. Retrieved August 28, 2022, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/treating/surgery.html

[15] Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Cancer prevention research. In Johns Hopkins Medicine (Author), The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center. Retrieved August 27, 2022, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/cancers_we_treat/clinical_cancer_genetics/research.html

[16] World Health Organization. (2020, December). Pancreas [Image; PDF].

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/13-Pancreas-fact-sheet.pdf